The Challenge of Designing for a Moving Target

Every AV project starts with uncertainty.

The architect's floor plan is at 50%. The interior designer hasn't finalized furniture. The client is still debating whether that corner space should be a huddle room or a phone booth. Meanwhile, someone needs to put a number on the AV budget. And that number will follow the project through permitting, financing, and construction.

This is the reality of specifying audiovisual systems for new construction or major renovations. You're designing for a building that doesn't exist yet, with stakeholders who are still making up their minds.

The firms that navigate this well produce spaces where technology feels intentional. The ones that don't end up with cable trays that dead-end into walls, displays mounted where the afternoon sun blinds everyone, and budgets that blow up during the final month of construction.

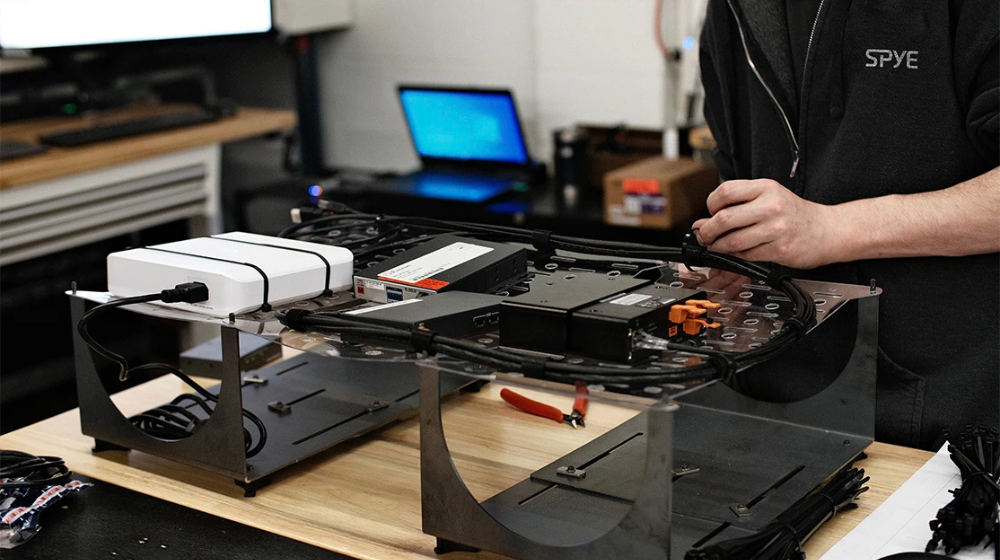

At Spye, we've spent over two decades helping architects, developers, and corporate real estate teams work through this process. What we've learned is that early coordination doesn't just prevent problems. It unlocks better outcomes that wouldn't be possible if AV is treated as a late add-on.

Getting in the Room Early

The biggest mistake we see is bringing the AV integrator in after design development is complete.

By then, the structural grid is locked. Ceiling heights are set. The electrical engineer has already sized panels and distributed circuits. The window wall is going exactly where it's going.

None of these decisions are wrong. But each one constrains what's possible with AV. If no one is thinking about sightlines, ambient light, acoustic isolation, or power density during schematic design, you end up with technology that fights the architecture instead of supporting it.

We push to be part of the conversation early, even when the floor plan is still a napkin sketch. At this stage, the questions aren't about specific equipment. They're about intent.

What kinds of meetings will happen in this space? Who's the primary audience? How much flexibility does the client actually need versus how much are they asking for out of habit? What's their tolerance for visible technology?

These conversations shape everything that follows. A boardroom designed for hybrid investor presentations has different requirements than a training room that occasionally hosts town halls. A lobby video wall meant to impress visitors is a different beast than an operations display that needs to run around the clock without image retention.

Designing in Pencil

One concept we use internally is "designing in pencil."

Early in a project, nothing is permanent. The integrator's job is to provide enough detail for cost planning and coordination without locking in decisions that might need to change as the design evolves.

This means developing AV layouts that can flex with the architecture. If the conference room shrinks by four feet during design development, the display size and camera placement need to adapt. If the client decides to add glass partitions, acoustic and lighting strategies have to shift. If IT changes the network topology, the AV backbone may need rerouting.

What we deliver at schematic design isn't a final equipment list. It's a framework.

That framework includes room-by-room narratives describing what each space needs to accomplish. It includes rough equipment categories with allowances for cost modeling. It spells out infrastructure requirements like conduit, power, data, and structural support that need coordination with other trades. And it identifies key architectural dependencies such as ceiling heights, sightlines, window placement, and acoustic ratings.

This gives the architect and contractor something to build around without forcing premature decisions on equipment that might change six months from now.

Coordination Across Trades

AV doesn't exist in isolation. Our systems touch electrical, mechanical, structural, millwork, furniture, IT, and security.

A project with poor cross-trade coordination shows it immediately. Displays fighting HVAC diffusers for ceiling space. Speakers competing with fire suppression heads. Control panels mounted where furniture blocks access.

We've found that the best results come from integrators who understand how to read a full set of construction documents and speak the language of other trades. That means marking up architectural sheets with AV rough-in locations. It means issuing coordination drawings that show exactly where conduit needs to stub up through the floor or drop through the ceiling. And it means attending owner-architect-contractor meetings to resolve conflicts before they become change orders.

On a recent Midwest headquarters project, we identified during design development that the architect's ceiling plan didn't leave clearance for the microphone arrays needed in a large divisible meeting room. Catching it early meant we could work with the mechanical engineer to shift a duct run by eighteen inches. The alternative would have been field-modifying the installation months later at triple the cost.

That kind of coordination doesn't happen if the AV integrator shows up after the ceiling grid is already installed.

The Budget Conversation

Clients often want a hard number before the design is finished. That's understandable. They have financing to secure and boards to satisfy.

But AV budgets at schematic design are inherently soft. The real question is whether the allowance is in the right order of magnitude and whether it aligns with the client's expectations.

We approach early budgets as ranges, not fixed bids. A typical format includes three tiers.

The base scope represents the minimum AV investment to make the space functional for its intended use. The target scope reflects what we'd recommend given the client's stated goals and the building's design intent. The stretch scope covers enhancements that would elevate the experience but aren't essential.

This structure lets the project team make informed tradeoffs as the design develops. If the base build comes in over budget, they can see where AV sits relative to other essentials. If there's room to invest, they have a roadmap for where that money could go.

It also protects against a common failure mode where AV gets value-engineered at the last minute. When the budget is transparent and tied to specific outcomes, it's harder for someone to cut 30% without understanding what they're giving up.

What Changes Between Schematic Design and Construction Documents

As the project matures, so does the AV documentation.

By the time construction documents are issued, we've moved from allowances to specified equipment. From conceptual layouts to coordinated shop drawings. From general infrastructure notes to precise conduit schedules and circuit loads.

The goal is to eliminate ambiguity before the electrician pulls the first wire. Every display has a specified mounting height. Every rack has a dimensioned footprint. Every low-voltage pathway is coordinated with the reflected ceiling plan.

It also means ongoing communication with the general contractor, architect, and owner's rep. Construction documents aren't the end of design. They're the baseline. Changes will happen. Substitutions will be requested.

The integrator's job is to evaluate those changes quickly and honestly, distinguishing between swaps that don't affect performance and those that compromise the system.

Staying Engaged Through Construction and Commissioning

Some integrators disappear between the bid and the installation.

We've seen projects where the AV firm showed up on move-in week, discovered half the infrastructure was installed incorrectly, and scrambled to make it work. The client ends up paying twice. Once for the work that was done wrong, and again for the fixes.

At Spye, we stay engaged through construction administration. We review submittals. We conduct site walks during critical phases. We attend coordination meetings with the general contractor. By the time our install crews arrive, we've already resolved most of the surprises.

Commissioning is where everything gets tested. Every display powered on. Every microphone calibrated. Every control interface programmed and verified against the client's actual workflows.

We don't consider a project complete until the end users have walked through their spaces and confirmed the systems do what they expected. Not just what the drawings showed.

And even then, we're not finished. Buildings evolve. Organizations reorganize. Technology advances. The service relationship that starts at commissioning is what keeps systems performing reliably five and ten years later.

The Payoff of Early Engagement

When AV is integrated thoughtfully from the start, the results are hard to miss.

The technology recedes into the architecture. Meetings start on time because the interface makes sense. Remote participants feel present because the cameras and microphones were positioned for them. Visitors notice the lobby display without noticing the infrastructure behind it.

These outcomes don't happen by accident. They happen because someone was thinking about AV when the building was still lines on paper.

Let's Start the Conversation Early

Spye helps teams translate early design intent into a real, buildable scope of work. Then we stay engaged through construction, commissioning, and long-term service.